“Bitches and Snitches that is what America is”–Bill Maher Comedian

In a recent Twitter/X Space hosted by Dr. Liza Dunn, a compelling dialogue unfolded, with Dr. Norman Clement delving into the contentious waters of positive eugenics. The discussion was deeply rooted in the themes of the iconic film “Gattaca,” while also drawing parallels with the historical legal precedent set by Buck v. Bell, underscoring the timeless relevance of these debates. (https://x.com/i/spaces/1vAGROAVlVXJl/peek)

The Overton Window, a conceptual framework for understanding shifts in public acceptability, starkly illustrates how genetic engineering has transitioned from the realm of science fiction to a palpable, present-day reality. Once considered a speculative horror, technologies like CRISPR and genetic screening through IVF now allow us to manipulate human genetics, potentially ushering in an era where diversity could be sacrificed for uniformity. In “Gattaca,” this future is vividly painted in a society divided into “Valids”, those humans genetically enhanced, and “In-Valids”, those humans born naturally, highlighting the potential for a new form of societal schism based on genetic privilege.

Dr. Clement dissected positive eugenics, explaining how this practice subtly encourages the proliferation of traits deemed “desirable” by society. But beneath this veneer of progress lies a troubling ethical quagmire. Who, after all, decides what traits are worth promoting? This practice, while cloaked in the language of improvement, risks reviving ancient biases, reducing the mosaic of human life to a monotonous canvas of genetic conformity.

“Gattaca” serves as a poignant narrative against this backdrop. Vincent Freeman, an “In-Valid,” challenges the genetic hierarchy. His life story is a beacon of human spirit, demonstrating that determination, courage, and ambition are not the products of genetic engineering but of something far more profound and intangible. One of the film’s most memorable scenes involves a childhood swimming race where Vincent, against all odds, outswims his genetically superior brother, Anton. Reflecting on this victory, Vincent muses, “…the impossible happened. It was the moment that made everything else possible.” This moment was not just a physical triumph but a declaration of psychological liberation from the shackles of genetic determinism. Vincent further explains his life philosophy during another race with Anton, saying, “This is how I did it, Anton – I never saved anything for the swim back.” This statement is emblematic of his total commitment to his dreams, a stark contrast to the cautious, predetermined lives of the “Valids”. Vincent’s journey is a narrative of humanism, a celebration of the indomitable spirit that transcends the confines of genetic code.

“They’ve got you looking so hard for any flaw, that after a while that’s all that you see.”–GATTACA

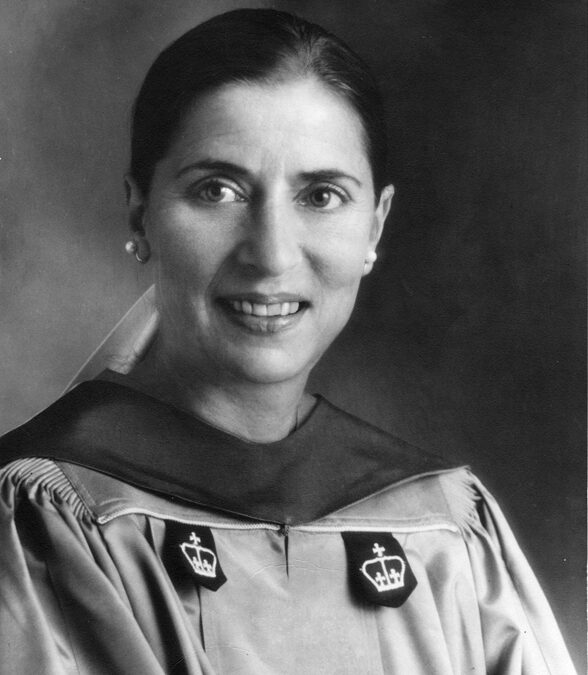

The Spaces conversation then turned historical with the mention of Buck v. Bell, where the U.S. Supreme Court in 1927 endorsed compulsory sterilization, with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. chillingly stating, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” The Buck v. Bell case is a grim reminder of how far society has gone in the name of eugenics, illustrating the potential for science and policy to become tools of oppression when stripped of ethical considerations. But how does this explain Ruth Bader Ginsburg, often affectionately referred to as “Notorious RBG,” who was a titan in the legal world whose stature belied her formidable influence. Standing at just five feet one, she managed to outmaneuver and outvote her nine Supreme Court colleagues, a majority of whom were men, on multiple landmark decisions.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, known as “Notorious RBG,” was a legal strategist whose impact on American law was profound. Her approach to legal advocacy was characterized by strategic case selection, where she picked battles that could systematically dismantle gender discrimination. Early in her career, she chose cases like Reed v. Reed to challenge blatantly unfair laws, laying down precedents for broader equality. Ginsburg was a proponent of incremental change, understanding that sweeping reforms were less likely to endure. She argued cases where men were victims of sex discrimination, like Frontiero v. Richardson, to demonstrate the universal harm of gender stereotypes. Her writing was both precise and persuasive, weaving historical context and social science into her arguments, which was crucial in her Supreme Court opinions. She was also adept at forming coalitions on the court, knowing when to push or compromise to sway votes, as seen in United States v. Virginia.

Justice Ginsburg’s dissents were not just disagreements but strategic seeds for future legal victories, her dissent in Ledbetter v. Goodyear directly led to legislative action. She used her public platform to educate and advocate, shaping public opinion to support her legal positions. She was unique in considering comparative law from around the world, bringing an international perspective to U.S. jurisprudence, as seen in her concurring opinion in Lawrence v. Texas. Her patience and timing were key as she waited for the right case or the right moment in history or court composition to push for significant change. Through her methods, Ginsburg didn’t just aim to win cases but sought to lay the groundwork for enduring legal and social progress, demonstrating that legal strategy is as much about the long game as it is about the immediate fight.

Dr. Clement warned to the Spaces Audience that although positive eugenics might aim for benign outcomes, it opens a Pandora’s box of ethical dilemmas. How can we safeguard against the emergence of a genetic caste system? How do we value the rich tapestry of human diversity over a quest for genetic “perfection”? These questions demand not just regulatory solutions but a profound moral reflection on inclusivity and the sanctity of human variation.

The ethical landscape of genetic engineering is intricate, filled with questions of consent, especially when modifications affect future generations, and concerns over equity as the cost of genetic enhancements could widen social divides. There’s also the looming threat of losing genetic diversity, which is crucial for human resilience. Regulation may be vital, yet without a cultural shift towards valuing diversity as strength, these legal frameworks might fall short. Cultural and religious viewpoints add further layers to this discourse, challenging us to consider whether genetic manipulation oversteps into sacred or natural domains.

The promise of genetic engineering is undeniable with a potential to eradicate hereditary diseases, and enhance human capabilities. Yet, as “Gattaca” so vividly warns, unchecked technological ambition could lead to a world where humanity’s soul is traded for genetic conformity. Dr. Clement ended the session with a call to action, we must advocate for humanism over hubris, diversity over uniform perfection, ensuring that the march of science does not eclipse the essence of what makes us human. Ultimately, “Gattaca” stands as both a cautionary beacon and an ode to human potential. Vincent Freeman’s triumph is not merely personal, it’s a universal cry that our spirit, our drive, our very humanity, are not defined by our genes but by our choices and our unyielding pursuit of what makes life meaningful. As we navigate this brave new world of genetic possibility, we must remember, there is no gene for the human spirit.

Dr. Anand received an honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy where he utilized regional anesthesia and pain management to treat soldiers injured in combat at Walter Reed Hospital. The Author is passionate about medical research and biotechnological innovation in the fields of 3D printing, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Dr. Anand was convicted through gross government misconduct and is now serving a 14 year sentence in prison. He will still be contributing articles to Doctorsofcourage to help with the mission to get the CSA repealed and all doctors expunged of their convictions, back in practice, and pain management restored.

So much good can come from CRISPR and genetic engineering. My grandaughter has Cystic Fibrosis. They already have created the genetic engineering on one gene for a rare CF disease, which will make it disappear. She has the most common gene, so they are still working on that, but there is hope for the future in its end. My husband has a genetic disease called choroideremia, which causes blindness. They are working on gene treatments for that as well, and will hopefully bring that disease to an end in the future. Granted, the use of anything can be for evil as well as for good. It is the responsibility of those in charge to follow God’s laws.

But I don’t think genetic engineering is what we need to worry about. IMO, it is AI. We have built another Tower of Babel, declaring us to be like God through AI. God will not allow this. The destruction of most of humanity, leaving only a remnant to live like they did back in Neanderthal days, and as many past movies have been about, is more probably our future. Just my opinion.

As one who habitually observes the universe through the harsh lens of Natural Selection and Evolution, I am skeptical of the thought that genetic selection by Homo sapiens, upon Homo sapiens, may yield outcomes, the positive nature of which could be proven by genetic sustainability over millenia… though the short-term outcome that the involved individual may *feel* God-like may be readily achieved.