As expected, physician organizations are jumping on board with the national anti-pain management fervor set off by the CDC Opioid Guidelines. In the June 15, 2016 American Family Physician, the publication of the American Academy of Family Physicians, is the headline article “Weighing the Risks and Benefits of Chronic Opioid Therapy” by Anna Lembke, MD, Keith Humphreys, PhD, and Jordan Newmark, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California (psychiatry and anesthesiology/pain management departments, not family medicine by the way).

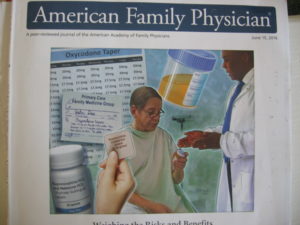

Cover of AFP magazine

The picture on the front cover of the publication headlining the article says it all. The picture includes:

1. Oxycodone Taper prescription instructions with a 2 ½ milligram per month reduction program in the background.

2. A urine collection cup for urine drug screens in the top right corner.

3. A bottle of Buprenorphine/ Naloxone sublinquals or a transdermal patch bottom left.

4. Patient is in the center looking unsure and uncomfortable.

5. A doctor standing over him trying to cover up what he is doing with an authoritative explanation.

The Big Question

One of the questions that always comes up on any chronic pain patient support group is: Why aren’t doctors coming together to support us? Well, here is the one organization that should be because it is independent family physicians that are being singled out by the Justice Department, charged as criminals, and ruined financially, professionally and personally. So what are they doing?

First, the purpose of AFP is stated “to serve the medical profession and provide continuing medical education (CME)”. CME objectives are (paraphrased): To provide updates on the diagnosis and treatment of clinical conditions managed by family physicians, reference citations, balanced discussions, and evidence-based guidelines.

Pure Propaganda

Let me state that I didn’t even get to the article yet, and I can say the review of this is going to be pure government propaganda. In the editorial by Deborah Dowell, MD, and Tamara Haegerich, PhD, they make the statement in the first paragraph that “it is unclear how effective long-term opioid therapy is for managing pain.” Would anyone in chronic pain like to step and tell them how effective opioid therapy is?

They make the statement that “As many as one in four patients receiving long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain in primary care settings has opioid use disorder.” And they quote statistics of people dying from opioid-related causes, most of which are caused by the government actions against legitimate pain management today. According to the American Psychiatric Association, the 12-month prevalence of opioid use disorder is approximately 0.37% among adults age 18 years and older in the community population (Compton et al. 2007). That is a far cry from 25% as stated here.

How can we coordinate this vast difference in percentages? It’s easy. The government, through the new CDC guidelines, is moving anyone that is dependent on opioids for control of their chronic pain as now diagnosed with “substance use disorder”. Substance use disorder in DSM-5 combines the DSM-IV categories of substance abuse and substance dependence into a single disorder measured on a continuum from mild to severe. Each substance is addressed as a separate “use disorder” which would include the “opioid use disorder” term used here. However, the main criteria which supposedly delineates opioid use disorder—a problematic pattern of use leading to impairment—is now only a part of the diagnostic criteria. Simple dependence which happens normally after 3 months of use will give a patient that diagnosis now, as evidenced by Oregon’s new Opiate Prescribing Guidelines that more states will probably adopt.

The actual diagnostic criteria for “opioid use disorder” are:

A problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

- Opioids are often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the opioid, use the opioid, or recover from its effects.

- Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use opioids.

- Recurrent opioid use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

- Continued opioid use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of opioids.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of opioid use.

- Recurrent opioid use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Continued opioid use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance.

- Tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

- A need for markedly increased amounts of opioids to achieve intoxication or desired effect.

- A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of an opioid

- Note: This criterion is not considered to be met for those taking opioids solely under appropriate medical supervision.

- Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following:

- The characteristic opioid withdrawal syndrome (refer to Criteria A and B of the criteria set for opioid withdrawal).

- Opioids (or a closely related substance) are taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms.

The authors’ response to the CDC guidelines were to say “This guideline is intended to help clinicians decide whether and how to prescribe opioids for chronic pain; offer safer, more effective care for patients with chronic pain; improve clinician-patient communication; and prevent opioid use disorder and opioid-related overdose.” They then go into enumerating the “important points that can help clinicians make treatment decisions” such as:

- Nonopioid therapy is preferred for management of chronic pain. Opioids should not be used as routine therapy outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, or end-of-life care. When used, they should be combined with other therapies.

- When opioids are used, the lowest effective dosage should be prescribed.

- Clinicians should use caution when prescribing opioids, closely monitor all patients, and continue therapy only after reevaluating the patient to determine benefits vs. risks.

The full CDC guideline is available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm

Another editorial by Patrice A. Harris, MD, MA entitled “The Opioid Epidemic: AMA’s Response” is pushing the currently politically-motivated acceptable government solution to the opioid epidemic, i.e. put everyone on the latest, more addictive opioid—buprenorphine/ naloxone. The politics is obvious, with her stating that the AMA is working with the National Governors Association and other leading stakeholders as well as the Obama administration. Recommended solutions are more physician training and increasing the number of physicians certified to prescribe buprenorphine or naloxone. She also states that “the AMA largely supports the CDC guidance” but then goes into concerns about the recommendations. However, there are no stated solutions to those concerns, just “wait and see”.

On their CME Quiz questions, the question about the article on Chronic Opioid Therapy is: Which one of the following formulations should be considered when initiating chronic opioid therapy in a patient at risk of opioid use disorder?

- Transdermal buprenorphine

- Transdermal fentanyl

- Methadone

- Morphine.

And the answer is…drum roll… A. Transdermal buprenorphine. I.e. The latest and greatest opioid giving a high 4x that of OxyContin to addicts.

So now let’s look at the article “Weighing the Risks and Benefits of Chronic Opioid Therapy”, dissect it, and read between the lines. The article can be found at: http://www.aafp.org/afp/2016/0615/p982.html. The cost for access to the article is $14.95.

The article starts out with the premise currently pushed by the government today: that the use of chronic opioid therapy for chronic pain is not supported by evidence, and the risks might outweigh the benefits. So right from the start, family physicians are warned that they are treading on quicksand if they choose to treat their patients with long-term opioid therapy, and they will get no support from their association. They also push the use of buprenorphine for patients at risk for opioid use disorder, which is pretty much everyone on an opiate longer than 3 months. They do open the door for treatment, however, by stating:

“Chronic opioid therapy benefits some patients with chronic pain.” And they urge physicians “to individualize therapy based on a review of the patient’s potential risks, benefits, side effects, and functional assessments, and to monitor ongoing therapy accordingly.”

But I’m afraid the effect of family physicians using this article as a basis for treatment is just putting more of them in the judicial noose.

“Recent reports indicate higher rates of opioid use disorder in this population [patients receiving opioids from a licensed physician for treatment of a medical condition] than previously assumed, with some studies finding prevalence rates as high as 50% in patients receiving chronic opioid therapy.” “Patients receiving opioid therapy for more than 90 days at doses of more than 120 MME (morphine milligram equivalent) are more than 100 times as likely to develop opioid use disorder as patients who do not receive opioids for similar conditions.”

But then they recommend to physicians for them to not suddenly remove patients from opioid therapy if they are found to have opioid use disorder. Either these authors are so protected from reality by academia, or there is a government agenda here. (Pardon my paranoia). In real life, if a doctor diagnoses a case of opioid use disorder, or even if one of his patients has a “red flag” the doctor doesn’t even know about, and he prescribes even one day more of an opioid, he is open to charges by the government of practicing “outside legitimate medical practice”.

But then they recommend to physicians for them to not suddenly remove patients from opioid therapy if they are found to have opioid use disorder. Either these authors are so protected from reality by academia, or there is a government agenda here. (Pardon my paranoia). In real life, if a doctor diagnoses a case of opioid use disorder, or even if one of his patients has a “red flag” the doctor doesn’t even know about, and he prescribes even one day more of an opioid, he is open to charges by the government of practicing “outside legitimate medical practice”.

And finally, on page 1042 we find the AFP Practice Guidelines based on the CDC Guidelines.

Key Points for Practice (identified as coming from the AFP Editors):

-

Chronic pain should be managed primarily with nonpharmacologic therapy or with medications other than opioids

-

Physicians should routinely discuss the risks and benefits of therapy and the mutual responsibility to mitigate risk with patients who are receiving opioids

-

When opioids are prescribed, they should be titrated to the lowest effective dosage.

Treatment should be offered or arranged for patients with opioid use disorder

Even though the statistics quoted are that the prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the US is approximately 11% and that as many as 43% experience daily pain, the AAFP reviewed the CDC guideline and gave it an affirmation of value.

I predict that the effect of the medical profession being forced to use this guideline is more addiction and more death due to opiates. The reason for this prediction is that, as a result of the current addiction situation, the government has put the blame on long-acting opiates. But the long-acting opiates are not to blame. Instead, as shown by studies done during the development of the long-acting opiates, keeping the levels constant in the bloodstream instead of the too much-not enough treatment of the short-acting opiates actually lowers the milligrams required to achieve pain relief. The problem with the long-acting opiates is when they are ground up and turned into short-acting by the addict. Chronic pain patients don’t do that. Now the problem with prescribing short-acting is that more are given out and patients then have access to using some and selling some. I anticipate more doctors will be charged with criminal activity because of this. But maybe that’s the plan all along.

Linda Cheek is a teacher and disenfranchised medical doctor, turned activist, author, and speaker. A victim of prosecutorial misconduct and outright law-breaking of the government agencies DEA, DHHS, and DOJ, she hopes to be a part of exonerating all doctors illegally attacked through the Controlled Substance Act. She holds the key to success, as she can offset the government propaganda that drugs cause addiction with the truth: The REAL Cause of Drug Abuse.

Get a free gift to learn how the government is breaking the law to attack your doctor: Click here to get my free gift

Thank you for your support but sadly I know it means nothing to those in power those withholding the power to change what is happening to innocent pain patients in our country that are so easily inflicting the torture of unrelieved severe pain on chronic intractable pain patients & their families. Patients like myself that have been stable on high dose opioids for over 10+years. Stable prescribed the same dose regimen for 10 years without increase or negative side effects. The last 10 years of pain relief have given me a life worth living have been mine and my families happiest & most pain relieved years of my life because when pain is reduced it provides a quality of life that is unattainable when pain goes unrelieved. When the disease state of chronic pain sets in it creates changes in your bodies function that once damaged from unrelieved pain are no longer fixable. You can only relieve the symptoms of pain but not cure or remove it. Opioid pain medications are not only the best available medications available but will not cause any damage to the body because naturally we have opioid receptors in our bodies a sure sign our bodies & nature were designed to work together. Opioids have been giving pain relief for the last 5000+ years. No matter what if people want to abuse drugs they will as they always have regardless of laws or limits used to try to control them, but in this process hurting pain patients doesn’t serve any purpose but to increase the suffering of people already struggling in life to be kicked down again.

BUT & here is the big BUT in all of this. No one wants to know or if they do listen (rarely) they put a label of addict on pain patients because of what is being said about pain patients in the media, by drug rehab docs with strong bias against any use of opioids & just happen to be the largest contributors to the CDC guidelines say if not the only, then with opioid phobic doctors influenced by poor reports & poorly done bias studies only focusing on the small amount of failures. The 2% of chronic pain patients with opioid treatments instead of focusing on the facts that 98% of pain patients are doing well with opioid pain medications how they are living better lives, but they throw all of that out to focus only on the 2% suffering with abuse & addiction to stack the deck in their favor & guess what it is working pretty well for them. The government agencies for a multitude of reasons continue to ignore pain patients & at the root of it all is greed. It’s all being done without ever knowing a thing about the pain patients they are condemning to suffer in pain & die without ever reading any of our medical records talking to us or our families or our pain management doctors. Medical records filled with proof of illness & injury, proof of pain & pain relief & with pain relieved better quality of life for patients & family strictly because of pain relief provided with opioid pain medications. Records to show NO SIGNS OF ANY ABUSE NO SIGN OF ADDICTION & NO SIGN OF DIVERSION BUT NONE OF THOSE LEADING THIS CHARGE THAT JUST SO HAPPEN TO ALSO BE PROFITTING GREATLY FROM THIS FALSE LABELING OF INNOCENT RESPONSIBLE CHRONIC PAIN PATIENTS UTILIZING OPIOID PAIN MEDICATIONS ARE COMPLETELY UNWILLING TO SEE, HEAR OR SPEAK TO US. UNLESS IT IS TO PUT PAIN PATIENTS IN THE SAME CATEGORY WITH DRUG ADDICTS. BECAUSE IF THEY DON’T IGNORE US THEY WOULD HAVE TO STOP THE TORTURE THEY ARE INFLICTING ON INNOCENT LIVES. THEY COULD NO LONGER ALLOW US TO BE THE COLLATERAL DAMAGE IN THIS WAR ON DRUGS TURNED TO A WAR ON PAIN SUFFERERS & OPIOIDS FOR PROFITS. THEY HAVE TO IGNORE OUR CRIES FOR HELP IGNORE THE FACTS WE ARE KILLING OURSELVES FROM UNRELIEVED PAIN DYING EVERY DAY OR RISK OF BEING EXPOSED FOR THE TORTURE, DEATHS, & SUICIDES OF PAIN PATIENTS SO THEY COULD PROFIT. THERE GREED THEIR DEALS ARE MORE IMPORTANT THEN THOSE LEFT TO SUFFER IN THEIR WAKE OF GREED.

ANYONE THINKS I AM WRONG THEN LOOK AROUND REALLY THINK ABOUT HOW OFTEN HAS ANYONE FROM THE PAIN PATIENT OR PAIN DOCTOR COMMUNITY BEEN INVOLVED IN ANY OF THIS PROCESS OTHER THEN TO BE PUBLICLY CONDEMNED FOR BEING IN PAIN COMPARED TO DRUG ADDICTS & PAIN DOCTORS COMPARED TO DRUG DEALERS. THEN THERE ARE THOSE THAT SHOULD BE SPEAKING OUT BUT AREN’T! WHY ISN’T BIG PHARMA ? WHY AREN’T THEY SCREAMING ABOUT LOST CUSTOMERS LOST PROFITS? WHY? BECAUSE THEY ARE PROFITTING WITH EVERYONE ELSE INVOLVED. THE GREED IN THIS COUNTRY HAS REACHED AN ALL TIME LOW THAT RUNS DEEP! WHEN GREED FOR PROFITS GOES THIS FAR WILLING TO CONDEMN INNOCENT PEOPLE TO LIVES OF CONSTANT UNRELENTING PAIN, SUFFERING & CAUSING FAR TOO MANY DEATHS & SUICIDES THEN THEY HAVE TO ALL BE WORKING TOGETHER & WITH A LITTLE RESEARCH YOU CAN FIND ALL THE CONNECTIONS THAT CONNECT ALL THE DOTS TO ONE GOAL PROFIT. THE DEATHS ARE CONTINUING TO RISE AS MORE PAIN PATIENTS ARE ABANDONED TO SUFFER WITHOUT THE MEDICAL CARE THEY HAD. THE MONEY TRAIN IS FAR MORE IMPORTANT THEN THE LIVES OF PEOPLE THEY DON’T KNOW, DON’T WANT TO KNOW & WHY THE PAIN COMMUNITY WILL CONTINUE TO BE IGNORED. WE WILL CONTINUE TO SUFFER, CONTINUE TO DIE. UNTIL THE PUBLIC IS WILLING TO SEE BEYOND THE PROPAGANDA THEY ARE BEING FLOODED WITH AT EVERY TURN BY A CONTROLLED MEDIA. UNTIL THE PUBLIC SEE THE TRUTH THAT THEY’VE BEEN MANIPULATED TO CONDEMN US THEY WILL CONTINUE TO ALLOW THIS MASS EXTERMINATION OF THE CHRONICALLY ILL FOR PROFIT. THE DRUG REHAB INDUSTRY CALLS AMONGST THEMSELVES “THE BUBBLE” & ‘THE GOLD MINE”. GREED IS ALWAYS HAS TRUMPED QUALITY OF LIFE FOR SOMEONE ELSE AS LONG AS IT DOESN’T EFFECT THEM THEY WON’T CARE HOW IT AFFECTS PAIN PATIENTS. ITS NOT PRETTY, ITS NOT NICE & IT’S NOT RIGHT BUT UNLESS THERE IS A MASS OF CITIZENS THAT DEMAND THE ABUSE & TORTURE TREATMENT OF PAIN PATIENTS BE STOPPED IN THE MEDIA SO THE GOVERNMENT CAN’T IGNORE US THIS WILL CONTINUE. EVENTUALLY IT WILL ONCE THEY HAVE MADE THEIR PROFITS ELIMINATED A LARGE PORTION OF THE CHRONICLLY ILL. THAT WILL ALSO BENEFIT THEIR PROFITS IN LESS PAY OUTS THEY WILL CLAIM THEY HAD NO IDEA NO INTENTION OF HARMING PAIN PATIENTS NO INTENTION OF CAUSING OUR DEATHS, BUT FOR THOSE THAT DON’T SURVIVE THIER BODIES GIVE OUT IN HEART ATTACKS & STROKES FROM UNRELIEVED PAIN & THOSE KILLING THEMSLEVES TO ESCAPE THE DAILY TORTURE OF SEVERE UNRELIEVED PAIN IT WON’T MATTER. BY TIME THEY STOP THIS GENOCIDE OF THE CHRONICALLY ILL & SERVED ITS PURPOSE IT WON’T MATTER BECAUSE ONCE YOU’RE DEAD DEAD IS DEAD. THERE WILL BE NO CHANCE TO GET PAIN RELIEF NO CHANCE TO RECOVER THEIR BROKEN LIVES BECAUSE PAIN RELIEF WITH OPIOID PAIN MEDICATIONS WERE TAKEN AWAY FROM RESPONSIBLE NOT ADDICTED PAIN SUFFERERS IT WON’T MATTER ANYMORE.

ALL I KNOW & KEEP SAYING IS KEEP TRYING TO GET YOUR VOICE HEARD! KEEP CONTACTING YOUR LOCAL NEWS & NEWSPAPERS! EVEN THOUGH IT ISN’T MUCH BUT IF THEY ACTUALLY PUT YOUR STORY IN YOUR LOCAL PAPER IT MIGHT REACH THAT ONE PERSON. THE ONE PERSON THAT CAN MAKE THE DIFFERENCE IN OUR MISERABLE PAIN FILLED LIVES. IT WORKED FOR ME I GOT MY STORY PUT ON THE COVER OF OUR NEWSPAPER! JUST THINK IF IT WAS ON THE COVER OF EVERY NEWSPAPER WE MIGHT GET TO THE RIGHT PEOPLE TO TURN THIS AROUND. RIGHT NOW THEIR GREED IS MORE IMPORTANT THEN OUR LIVES WE MUST FIND A WAY TO MAKE IT SEEN SO OUR LIVES ARE MORE IMPORTANT THEN THEIR GREED.

I totally agree with what you say. I hope to get the truth about the REAL cause of drug addiction in front of the American people. If everyone knows that the drugs don’t cause addiction, then the government can’t keep up the farce.

As a non-physician research analyst, webmaster and author with 20 years of experience in patient support, I interact every week with chronic neurological face pain patients. I would add a few footnotes to Dr. Cheek’s article.

I have read the CDC guidelines and the interim briefings generated by the consultants working group which wrote he guidelines. From this reading and other public commentaries, I offer the following as facts:

1. The CDC Consultants’ working group tasked with writing the guidelines failed to include a single board-certified pain management specialist who regularly serves chronic pain patients in practice. At least two meetings of this group were also closed to the public, directly violating Federal transparency laws applicable to FDA and CDC.

2. The scientific “evidence” given in support of the dose restrictions proposed by the guidelines is very weak and appears based primarily on an aggregation of four reports that in fact are internally contradictory if not outright invalid.

3. Despite receiving literally thousands of comments from the public, it appears that the consultants’ group completely ignored the voiced experience of chronic pain patients who have successfully used opioids for years at high but stable dose levels. Some of these patients experience physical dependency and withdrawal symptoms when forced off opioids, but the great majority of patients display none of the other behaviors imprecisely grouped in the DSM-5 criteria for Opioid Use Disorder.

4. Due to the current hysteria and propaganda being broadcast by DEA and the CDC itself, significant numbers of pain management doctors are being driven out of practice. Thousands of patients are being outright deserted to go through withdrawal while in abject agony, without medical assistance.

5. Opioid medications are almost never the treatment of first resort in chronic pain. Instead, such medications are used only after the failure of other therapies to provide adequate (or “any”) pain relief. In patients who use these medications with adequate initial screening for previous drug addiction issues and ongoing medical oversight, it is highly uncommon for the patient to spiral into drug addiction.

Given these factors, I believe it is ethically and legally imperative that the CDC guidelines be withdrawn immediately and rewritten. The guidelines need to reflect much better science as well as patient input as central influences in reaching an ethical balance between concerns for pain management and concerns for addiction issues. I call on all members of Doctors of Courage and all of the readers of this article to demand of their legislators at both State and Federal level that these steps be taken immediately. If such steps do not occur within the next few weeks, then I urge Doctors of Courage to find a legal firm and begin action to sue the CDC to force these steps. Plausible grounds might include active denial of medical care, patient abuse, and violation of the Americans With Disabilities Act, among others.

I applaud you, Dr. Lawhern, for your public statement.

Those parroting the standard anti-opioid (=Anti Chronic pain patient) is a large and growing thundering herd! It now includes the US Surgeon General who is sending a personal letter parroting the same old arguments to every prescribing physician in the US! When I reflect on what is going on, it becomes clear that there is currently a mass performance of a distinct medical syndrome that is targeting those with chronic pain and the few remaining doctors willing to treat them: We are witnessing a societal and institutional level of a psychiatric problem: Factitious Disease Imposed on Another.

Factitious because people with chronic pain are wrongfully being accused of having the attributes of an addict….when in fact there is rare overlap.

Factitious because the current hysteria diverts resources that should be used to treat legitimate addicts AND criminal recreational users who are probably at extremely high risk for fatal overdose, away from treatment of the real disease and into efforts that misbrand the chronic pain patient.

Imposed on Another because the chronic pain patient is having these wrongful attributes imposed on him/her without any justification and without properly INFORMED consent. (The least informed seem to be those who continue to impose the factitious findings on the legitimate chronic pain patient.)

The management of this psychiatric disorder, among others, consists of 2 steps: 1. Removal of the “Imposer” from any role in the medical care of the person who is labeled “Another” (Chronic pain patient in this situation). 2. Protection of the person designated “Another”, by COURT action if needed in the delivery of medical services.

So lets label the perpetrators of this institutional level societal juggernaut for what it is: The PSYCHIATRIC DISORDER of FACTITIOUS DISEASE IMPOSED ON ANOTHER!

To let the juggernaut persist and grow will lead to more torturous suffering among chronic pain patients. But it will also claim more innocent victims….like the woman in Florida who went to the Emergency Room complaining of chest pain, only to be misbranded a “drug-seeker”. She was escorted out of the ER, only to die of a pulmonary embolus…..while a nurse apparently continued to berate her as “faker”.