Metrics Without Meaning: The Dangerous Logic Behind Colossus and Mitchell Decision Point

The Rise of the Number-Crunchers

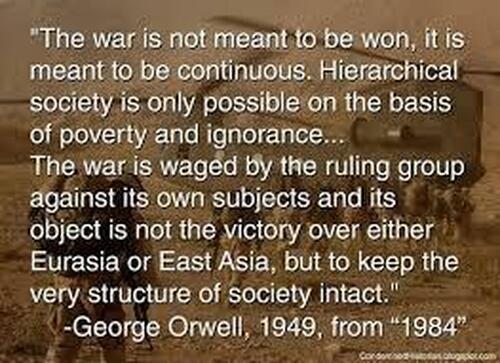

In the 1960s, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara became infamous for reducing the complexities of war into spreadsheets and body counts. His approach now known as the McNamara Fallacy (or quantitative fallacy) prioritized measurable data over intangible realities, leading to catastrophic misjudgments in Vietnam. Tragically, this same reductionist mindset has since infiltrated corporate boardrooms, government policy, and even the insurance industry, where algorithms like Colossus now decide the value of human suffering.

The late 20th century saw a seismic shift in business philosophy. As the middle class grappled with stagflation, corporations turned to consultants and efficiency experts, many freshly minted from business schools who saw employees not as assets but as line items to be cut. The result? A hollowed-out workforce, where foremen, middle managers, and skilled laborers were deemed expendable in the name of “shareholder value.”

Jack Welch, the CEO of General Electric, became the poster child for this movement. His ruthless cost-cutting and obsession with quarterly returns earned him Wall Street’s admiration until, years later, GE’s decline exposed the rot beneath the spreadsheet miracles. By the 1990s, 90% of CEOs had once risen through the ranks of their companies, by the 2000s, most were outsiders, parachuted in from consulting firms with little understanding of the businesses they were hired to gut.

Colossus: The Algorithm That Decides Your Pain and Suffering

This same quantitative obsession now governs how insurance companies handle injury claims. Colossus, a software program first adopted by Allstate in the 1990s, was designed to standardize payouts and minimize them. Similar programs like Claims Outcome Advisor and Claims IQ serve the same purpose by converting human suffering into a secret, rules-based numeric score that dictates what an injury is “worth.” In theory, there’s nothing wrong with quantifying damages—after all, courts do this every day. But when an opaque algorithm, designed to save insurers money, determines the value of a broken bone, chronic pain, or emotional trauma, the system is rigged from the start.

Here’s how it works:

After an accident, your lawyer notifies the insurance company. The insurer inputs details about your injuries into Colossus, which spits out a “reserve”—the amount they’re willing to pay. This reserve is often deliberately low, because insurers know most people won’t fight back. If your injuries worsen or require unexpected treatment? Too bad. The algorithm has already decided.

Mitchell Decision Point is the latest embodiment of a dangerous trend that began decades ago, the outsourcing of human judgment to algorithms under the guise of efficiency. Much like Colossus before it, Decision Point replaces human understanding of medical necessity with software that evaluates bills using opaque criteria. Billed as a cost-containment tool, it offers dashboards, benchmarking, and integration with claims systems to give adjusters “decision support.” But in practice, it empowers insurers to downplay or deny medical bills using a rules-based system that sees injured claimants as data, not people. What began as an attempt to control fraud has evolved into a model that too often undercuts legitimate care by privileging statistical norms over individual realities.

This mirrors the same McNamara fallacy that has hollowed out industries by reducing complex human conditions to measurable metrics while ignoring the immeasurable. When software is used to deny care based on averages rather than clinical nuance, it becomes less a tool of justice and more a mechanism of profit maximization. The promise of accuracy and consistency masks a deeper loss, the abandonment of human discernment in matters that demand empathy and context. Like Colossus, Decision Point doesn’t just make claims processing faster, it makes it colder, more detached, and less just. In the pursuit of efficiency, we risk creating systems that work perfectly on paper and fail spectacularly for people.

The Human Cost of Cold Calculations

The McNamara Fallacy teaches us that when we reduce life to numbers, we lose sight of reality. In Vietnam, body counts didn’t measure morale or political will. In business, quarterly profits didn’t account for employee loyalty or long-term innovation. And in insurance, Colossus doesn’t measure real pain, only what the corporation is willing to pay. We don’t need to abandon data entirely, but we must resist the tyranny of quantification. Whether in war, business, or law, human judgment must temper cold algorithms. Otherwise, we risk a world where suffering is just another line item, and fairness is sacrificed for efficiency. The solution isn’t a return to some mythical past, but a demand for balance. Let data inform—but never dictate—the value of a life, a worker, or a victim’s pain. Because in the end, not everything that counts can be counted.

From AI-driven hiring tools that reject qualified candidates to healthcare algorithms that deny coverage, the McNamara Fallacy is alive and well. If we don’t push back, we’ll find ourselves at the mercy of systems that see us not as people, but as inputs in a profit-maximizing equation. The lesson is clear: Beware those who would measure the unmeasurable and then claim the math doesn’t lie.

The Author received an honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy where he utilized regional anesthesia and pain management to treat soldiers injured in combat at Walter Reed Hospital. The Author is passionate about medical research and biotechnological innovation in the fields of 3D printing, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.