He found a little child on the beach who had made a small pit in the sand, and in his hand carried a seashell that he used as a little spoon. With the shell in his hand, he ran to the water and scooped out a spoonful of seawater. Then, he went back and poured it into his pit. And when St. Augustine beheld the child, he marveled and demanded to know what he was doing. The boy answered, “I am bringing all the water from the sea and pouring it into this pit.”

“What?” said St. Augustine, “It is impossible! How may it be done, since the sea is so great and large, and your pit and spoon are so small?”

“Yes, this is true,” said the little boy, “But, it would be faster and easier to move all the water from the great sea and pour it into this little pit then for you to grasp the mystery of the Trinity and His Divinity, for this mystery is greater and larger compared to your wit and intellect than the sea is compared to my little pit.” Then the child, who perhaps was an angel sent by God or the Christ Child himself, vanished leaving St. Augustine alone on the seashore with his thoughts.

— The Golden Legend by Jacobus De Voragine (1275 AD)

In L. Frank Baum’s classic, The Wizard of Oz, the great and powerful Oz is ultimately revealed to be a frail man pulling levers behind a curtain, projecting an illusion of omnipotence. Today, in the realm of healthcare justice, the curtain is digital and the wizard is Palantir Technologies, an artificial intelligence data analytics company whose healthcare fraud algorithms purports to see all, know all, and preempt fraud with oracular precision.

Palantir Technologies filed a patent in Great Britain titled, System for Detecting Health Care Fraud (Application number GB1404573.6, Publication number GB2514239, Date: 2014-11-19, Applicant: Palantir Technologies Inc. Inventors: Lekan Wang, Casey Ketterling, Christopher Ryan Luck, Michael Winlo) This patent application describes a computer-based system and methods for detecting health care fraud. The system integrates health care data from various sources (providers, insurers, pharmacies, public sources) and transforms it into a structured ontology. This data is then used to generate graphs and visualizations that highlight relationships and potential indicators of fraud. The system employs various metrics and triggers to automatically identify potential leads for investigation.

However, beneath the polished interface of its artificial intelligence platform, replete with glowing networks, pulsing red nodes, and graph-based ontologies, lies a profoundly troubling reality. Palantir’s artificial intelligence system misunderstands, and effectively nullifies, the very concept of moral agency. It replaces the human capacity for context-sensitive judgment with statistical suspicion and reduces the moral bedrock of justice, the ability to have done otherwise, to a probability score.

Centuries ago, philosophers grappled with a paradox: If God knows the future, do humans truly have free will? At the core of Western Civilization’s legal and ethical understanding of guilt lies the Principle of Alternate Possibilities (PAP), which states that a person is morally responsible for an action only if they could have chosen differently. PAP undergirds much of Western jurisprudence. Context is everything. But context is precisely what Palantir’s artificial intelligence algorithms omits.

Palantir’s artificial intelligence system, widely used by federal agencies and private insurers alike, ingests a deluge of data—insurance claims, pharmacy logs, public records—and “red flags” individuals whose behaviors deviate from established statistical norms. The threshold for suspicion is not intent, necessity, or clinical justification, but deviation i.e. too many prescriptions, too many patient referrals, too many specialist visits. Palantir’s artificial intelligence system does not ask why these outliers occur. Palantir’s AI does not consider whether a patient needed that care or whether a physician served a high-risk population. Palantir’s AI simply flags the anomaly and lets human interpreters, often prosecutors or investigators, fill in the blanks with assumptions of guilt.

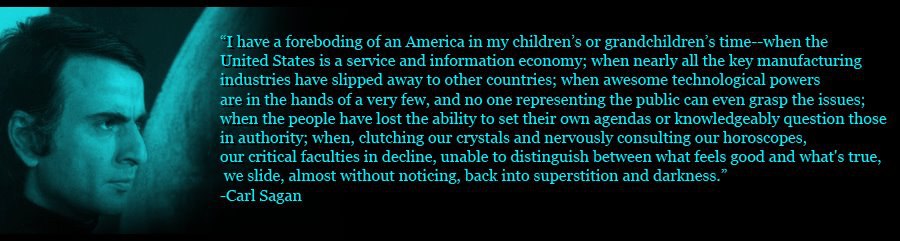

This silicon-based, mechanized approach to fraud detection evokes a digital revival of theological fatalism. Just as philosophers once questioned whether divine foreknowledge nullifies human freedom, Palantir AI’s mass surveillance system generates a paradox of predictive justice, where it claims omniscience through data analytics while simultaneously denying human individuals the opportunity to be judged as human agents capable of acting otherwise. In doing so, Palantir replaces legal adjudication with algorithmic fatalism. If Palantir’s AI system predicts fraud, then fraud, by definition, must have occurred.

The epistemological danger here is compounded by the illusion of scientific certainty. There are also unknown key threats including misuse (bad actors using AI for harm), misalignment (AI knowingly going against its developer’s intent), mistakes (AI causes harm without realizing it), and structural risks (failures that emerge from complex interactions between people, organizations, or systems). Palantir’s visualizations—complex graphs and red risk clusters—are not evidence in any traditional sense, but are persuasive aesthetics. Their power lies not in what they reveal, but in how convincingly they simulate knowledge. Judges and juries are shown images of sprawling networks connecting doctors to pharmacies to patients, often without any meaningful understanding of the thresholds, data biases, or AI algorithms that produced those connections. The medium becomes the message, and the message is guilt.

Worse still, the Palantir’s AI system is proprietary. Its AI algorithms are opaque and shielded from scrutiny. Criminal defense attorneys cannot interrogate how risk scores are calculated. Experts cannot evaluate false positives because the error rates are not publicly disclosed. Independent researchers cannot replicate or review its methodologies or ontologies. What Palantir offers is not science, but faith, a belief in the objectivity of a black box.

In Court, where lives and reputations hang in the balance, this should be unacceptable. Under the Daubert standard, expert evidence must be testable, peer-reviewed, and possess a known error rate. Palantir’s AI healthcare fraud algorithm meets none of these criteria. Its outputs are taken on trust, not merit, and its conclusions, delivered via dashboards and data visualizations, are treated as gospel even when their foundations are made of sand. This is not merely a technical flaw. It is Western Civilization’s philosophical collapse. Palantir’s AI algorithm itself cannot recognize alternate possibilities. It cannot entertain counterfactuals, weigh intent, or understand moral nuance. It is deterministic in structure and in output, yet it is used to determine whether human beings acted freely. The contradiction is glaring. A Palantir AI system that cannot act otherwise is deciding whether other human beings could have.

Like the child on the beach who scoops the ocean with a shell, Palantir’s AI algorithms attempt to reduce the sea of human behavior to a manageable pit of data. But human imagination, care, choice, and context are not easily quantified. Human life journeys are stories, not spreadsheets of data. When we entrust our systems of justice to AI algorithms that treat correlation as conviction, we are not fighting fraud, we are dismantling the very scaffolding that makes justice and reality possible. Philosopher Jean Baudrillard called this state, hyperreality.

Hyperreality captures a cultural condition where simulations and symbols no longer represent reality, they replace it. In a hyperreal state, consumerism thrives on sign exchange value, and brand names become markers of identity and worth, detached from any functional or emotional reality. Reality itself dissolves into endless reproductions, and fulfillment is sought not through authentic experience but through the consumption of stylized imitations. The end result is a blurring of fiction and fact, where the distinction between image and truth collapses, and the hyperreal becomes more convincing, and more desirable, than the real.

This condition has direct implications for artificial algorithmic systems like Palantir’s. These AI tools don’t just analyze data, they construct and project a version of reality, often with hidden assumptions and biases. The danger lies not merely in bias, but in unseen bias, the kind encoded in proprietary algorithms presented as objective truth. What’s needed is not the impossible promise of neutrality, but transparency and open configurability, allowing users to see, understand, and adjust the biases within. Only through decentralized, participatory models, ones that share not just code but trained weights and decision logic, can we challenge the illusion of algorithmic omniscience and reassert human agency in the hyperreal artificial intelligence systems that now shape our lives.

The metaphor of Wizard of Oz is apt. Palantir’s technology operates behind a curtain of proprietary secrecy, projecting power and certainty while concealing fragility and error. It dazzles those who gaze at its graphs but cannot withstand the light of critical scrutiny. The true danger is not that such Palantir AI systems exist, but that we humans defer to them. That we allow AI visual persuasion to replace reasoned human argument. That we accept AI predictive data analytics as proof.

In a world increasingly governed by artificial intelligence algorithms, we must remember what makes justice just. It is not the volume of data or the sophistication of the AI software. It is the ability to consider alternate possibilities, to contextualize decisions, and to respect the human agency of those we judge. Palantir’s AI healthcare fraud algorithm offers none of these. Until it does, we must pull back the curtain, and expose the illusion for what it is. Because the future of justice depends not on how well humanity predicts guilt, but on how fiercely humanity protects the freedom to choose otherwise.

The Author received an honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy where he utilized regional anesthesia and pain management to treat soldiers injured in combat at Walter Reed Hospital. The Author is passionate about medical research and biotechnological innovation in the fields of 3D printing, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks