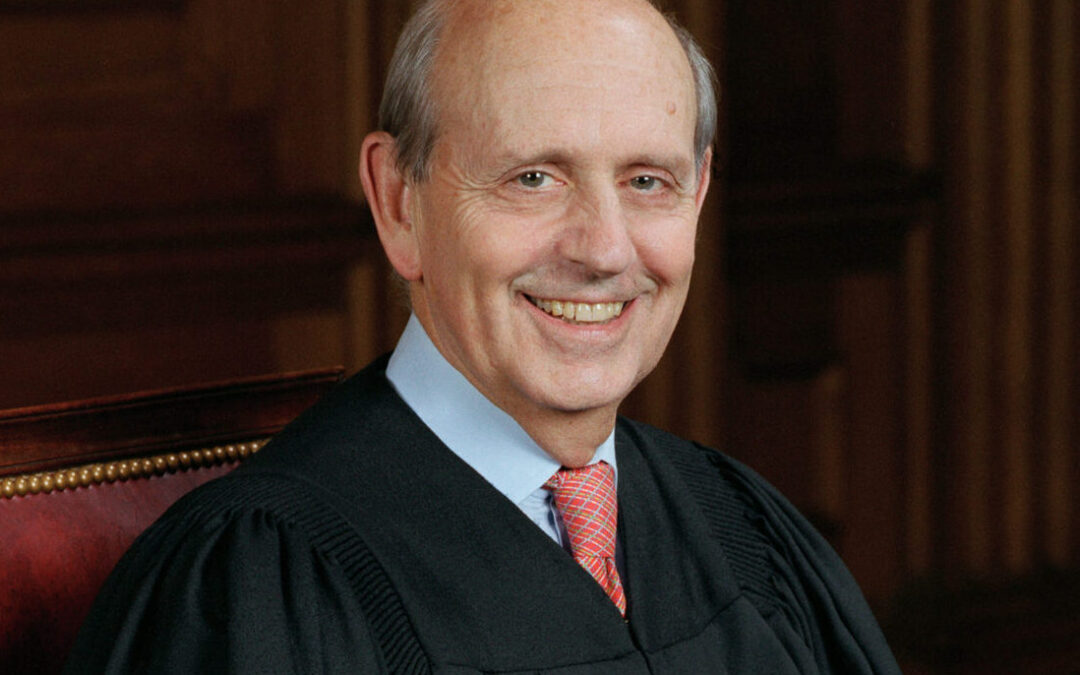

Ah, Justice Breyer. His farewell decision in Xiulu Ruan v. United States was hailed as a triumph for reason in an era of madness, giving doctors the breathing room to, you know, actually practice medicine without constantly fearing the government’s pitchforks. A unanimous 9-0 decision, mind you! Even Justice Thomas couldn’t find a way to disagree, and that’s saying something. Yet, here we are, with the Sixth Circuit discarding Breyer’s careful reasoning like an outdated medical chart, no longer relevant to their diagnosis of justice.

In Ruan, Justice Breyer generously offered the government a little reminder: If you’re going to convict a doctor of over-prescribing medication under 21 U.S.C. § 841, you need to prove that they “knowingly or intentionally” acted in an unauthorized manner. Seems simple enough, right? You know, prove that the doctor actually meant to break the law. Oh, and you can’t just put the doctor on trial for failing to be a “reasonable” doctor, as if there’s some ideal, perfectly cautious physician floating around like Goldilocks prescribing exactly the right amount of Oxycontin to exactly the right people at all times.

But the Sixth Circuit had other ideas. Forget Breyer’s emphasis on subjective intent. They’re more interested in good ol’ circumstantial evidence. Yes, because nothing says justice like piling up vague hints and red flags to convict someone, especially when it’s a doctor trying to balance the chaos of human suffering.

In a world where doctors are supposed to care about their patients, Dr. David Suetholz is apparently guilty of committing the most egregious sin: actually putting his patients first. His heartfelt defense that he was “treating his patients in the best way he knew how” and that there was no evidence of “nefarious” motives on his part seems to have fallen on deaf ears in the courtroom. Because, according to the Sixth Circuit, compassion and good faith don’t count for much when you dare to deviate from bureaucratically approved prescribing norms.

Dr. Suetholz’s argument was simple: He knew his patients, he understood their pain, and he made decisions based on their needs—not some checklist cooked up by faceless regulators. He didn’t set out to harm anyone. He wasn’t running a pill mill or profiteering from prescriptions. He “cared about his patients with every fiber of his being” and believed, in his professional judgment, that he was prescribing medication to genuinely help them. But no, that’s not good enough anymore, because subjective intent—the heart and soul of doctor-patient trust—apparently doesn’t matter.

Instead, the court waved off his defense, reducing his years of medical practice to a game of “gotcha” with circumstantial evidence. The prosecution and the judges seem to think that just because Dr. Suetholz didn’t follow every single procedural formality, he was somehow criminally negligent. Let’s be clear: this isn’t a case of someone who ignored his patients. Dr. Suetholz prescribed medications that were well within his medical purview. But now, doctors like him are held to rigid “objective criteria” that dictate the “legitimate medical purpose” and the “usual course” of practice. In other words, if you’re not prescribing exactly what’s on the insurance company playbook, you’re guilty of malpractice—or worse, a federal crime.

But what about the nuances of patient care? According to the court, Dr. Suetholz’s subjective belief that he was helping his patients didn’t matter. They cite the Moore case, which seem to suggest that “bad-apple” doctors can’t hide behind their personal judgment or good intentions. Bad apples? Really? Since when did caring too much become synonymous with being a bad doctor? Dr. Suetholz didn’t hide behind anything—he treated his patients the best way he knew how. Yet here we are, with his sincere efforts being reframed as criminal behavior because they didn’t perfectly align with Government unenumerated “objective” standards.

What’s worse is the court’s dismissal of his argument that he had no “nefarious” motives. The fact is, no one showed any evidence that Dr. Suetholz was out for personal gain, acting recklessly, or even deviating from the norm in bad faith. His patients had serious conditions—chronic pain, anxiety, panic attacks. He responded to their needs as any compassionate doctor would. And what did he get in return? A conviction that brands him a criminal for caring.

If we’re now convicting doctors for using their own judgment and prescribing with the best of intentions, what does that say about the future of patient care? Are doctors supposed to treat patients by following rigid algorithms, devoid of human empathy and individual decision-making? Dr. Suetholz’s case is a chilling reminder that the government seems to want robots, not doctors, who unquestioningly follow “accepted limits” rather than listen to their patients.

So here we are, punishing good doctors for their good faith. If caring deeply about your patients is the new crime, then the medical profession better brace for a long line of criminal indictments. Take Dr. Suetholz, for example. He was convicted of, among other things, prescribing the “strongest pill size you can get in Oxycontin” (I mean, cue the ominous music, right?). Sure, he prescribed 80-milligram Oxycontin pills to a patient in obvious need.

And let’s not forget the Sixth Circuit practically gasped at the sheer horror of Dr. Suetholz increasing a patients benzodiazepine prescription from a mere 15 pills to a jaw-dropping 120. Sure the patient had generalized anxiety and was suffering from panic attacks, but in this enlightened age, where anxiety magically vanishes with a couple of mindfulness exercises and chamomile tea, who needs such a “shocking” dose of medication? Dr. Suetholz had the audacity to prescribe benzodiazepines for panic attacks, a totally unheard-of practice in medicine (sarcasm intended). Not only that, but when patients urine test came back negative for the prescribed meds—possibly indicating that they weren’t even taking them properly—Dr. Suetholz still didn’t cut off the prescriptions immediately. Obviously, this meant to the Federal Court that the patient was probably selling the meds on the streets, right? Because what other explanation could there be? The Sixth Circuit was sure Dr. Suetholz should have known.

Justice Breyer’s unanimous opinion in Ruan demanded the government prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Dr. Suetholz knew he was acting improperly—subjective intent, folks!—but the Sixth Circuit was happy to lean on circumstantial evidence instead. They cited Suetholz’s “failure to adequately examine” his patients, “failure to enforce compliance,” and overall failure to be that mythical “reasonable” doctor that Breyer warned against. In doing so, they brushed aside Breyer’s rejection of holding doctors to the standard of some hypothetical “reasonable” physician.

So, where does that leave the rest of the medical profession? Well, over 3,000 doctors have already been convicted using this kind of evidence, meaning Breyer’s thoughtful ruling is being ignored on a daily basis. The next time you see a physician nervously tiptoeing around your symptoms like they’re walking through a minefield, remember to thank the courts for ensuring that every prescription is a potential federal indictment waiting to happen. Because nothing says “patient care” like doctors operating with one eye on the law and the other on the DEA.

The Author received an honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy where he utilized regional anesthesia and pain management to treat soldiers injured in combat at Walter Reed Hospital. The Author is passionate about medical research and biotechnological innovation in the fields of 3D printing, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Is anything being done to stop the DEA’s abuse and their criminally prosecution of doctors, really, 3000 doctors??!! Including my husband. We are awaiting our appeal and Ron Chapman II continues to represent him.

We, on doctorsofcourage, are the only ones doing anything that can be effective in ending the abuse. But few people are doing what is needed–to learn the truth and then teach it to others. All other advocacy groups are chasing rabbits that will get us nowhere. But to achieve the end of the attacks, get freedom, exoneration, and compensation to those attacked, and restore pain management in this country, people need to understand the REAL cause of addiction to end the propaganda. Otherwise, we have another 30 years (propaganda takes 50 years to be offset) to live through, and soon there will be no opioids available. So, if you want your husband freed and exonerated, and his profession restored, get signed up to take the ecourse. As his representative, you would be an ambassador, and it would be free of charge. But before I will start the next course, I need 10 people signed up.

Looks like it is time to challenge all the “red flags” that the DEA has created without any statutory authority and was backed up with the overturning Chevron Doctrine recently

How about doing away with all the attacks, get everyone charged exonerated and compensated, end the border crisis, save tax dollars, etc. The only way to do that is to repeal the CSA. Learn that no drug causes addiction. Anything less that that is a rabbit hole that will get us nowhere. It is only through the illegal use of the CSA that the government makes money by stealing from doctors. There is no constitutional right for the government to control anything we put into our body. Get behind us, spread the word. Anything else is a rabbit hole.